My latest think piece for Passenger Transport magazine argues that there are uncomfortable echoes of the 1948 rail nationalisation in the lack of clarity over what the railway is there to do for people, passengers and places and how in concrete terms it is going to do it. It makes the case for looking forward not backward this time around…

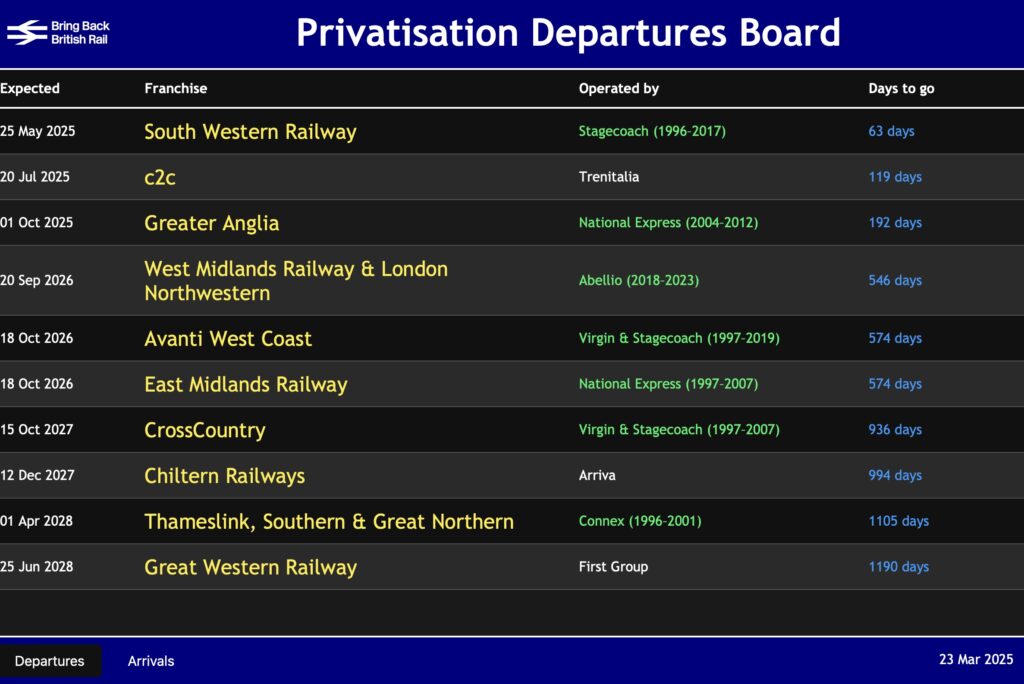

The interminable death throes of rail privatisation are finally coming to an end. The process of putting the railway back together again is very slowly pulling out of the siding. It really is happening now. An integrated and nationalised railway is going to replace the expensive pretence that a heavily subsidised public service can be made to behave like a free market. Government no longer has any tolerance for endless tinkering with a structure that has proved itself fundamentality incapable of providing a reliable railway at a price the nation can afford. A railway that has also been subject to periodic nervous breakdowns – from Hatfield and Railtrack going bust to persistent timetable meltdowns and staff shortage fiascos. The bar of the last chance saloon is finally closing and the financial engineers have been asked if they have got homes to go. Treasure island (as Britain was known to overseas franchise bidders) is closing its borders.

All well and good. But what happens now? Well we know that the initial focus is on gingerly rebuilding the custom and practice of operating an integrated railway again. This to be done through ‘alliances’ on select parts of the network where although infrastructure and operator are still separate entities there is no financialisation of the relationship. Instead there is a common goal of doing what’s best for the railway and its passengers. We know that the rail minister doesn’t want GBR to be a large organisation and the intention is that it will grow out of government, operators and Network Rail – rather than Network Rail turning into GBR. We know that the government doesn’t want open access passenger operators excessively freeloading and cherry picking at the state’s indirect expense. We also know it’s going to take time. Time for the franchises to expire, time to set GBR up and time for the railway to get used to being one team again. We know that the Government wants a single integrated GB railway – but it also favours Mayoral areas, with the ambition and resource, integrating the railway into their wider single integrated public transport networks. If you are a neat freak this seems incompatible. Scotland and Wales already have (to a greater or lesser extent) their own railway. There’s also London Overground and Merseyrail Electrics. Bee Rail is on the cards for Greater Manchester. Does this mean that GBR railways is really GB long distance and the English regional rail network that Mayoral authorities haven’t successfully claimed? The tensions are already apparent. This isn’t the big railway that railway folk were assuming. However, I believe it can work if a bigger vision is there – which I will come back to later.

So that’s what we know. What we don’t have yet is a sense of how this is going to work in practice. What it will look like and feel like for passengers? What will the structure and governance of GBR will be. If you are glass half full you would say caution and slowness makes sense given the complexities and that you don’t want the railway to perform worse before it gets better. If you are less generous you might argue that the nature of rail reform is so far characterised by lofty high level adjectives and insular railway organisational pre-occupations. Missing in the middle is a vision of what this new railway will actually do for passengers and places and what the proof points are along the way. And although it feels like there’s lots of time for steady as we go, there’s also an argument for moving faster. Because the world is an uncertain place and politics abhors a vacuum. Because there needs to be some concrete sense for passengers, places and the workforce of where this is all heading.

In some ways there are some uncomfortable echoes of the 1948 rail nationalisation. There the railway was exhausted by war rather than rail privatisation. There was also a similar conservatism among the railway establishment who succeeded in translating the preceding division of the railway into four large companies into the new British Railways. This was a ‘Morrisonian’ form of nationalisation where publicly owned industries were still to be run by the same kind of businessmen and specialists as they were before they were nationalised. Meet the new boss, same as the old boss. For the railways this meant it took a long time before British Rail (as it became) started living up to its name and stopped organising itself around railway operational geography and started to align themselves with the services the railway offers to the people and places it serves – namely regional, inter city, London and the south east and freight. So if we don’t want 1948 again what could a vision for the future of an operationally integrated and publicly owned railway look like?

Well how about a simple and compelling fares offer? How about a GB version of Germany’s Bahn Card? For an annual fee you get a third or a half off? A good proportion of the population can get a third off anyway through one of a myriad range of national railcards so why not extend the privilege (you could charge less for the card for concessionary groups if you wanted). Also use the card to make public ownership more tangible and associated with the more positive aspects of life – leisure travel offers, opportunities to get involved and news about how the network is developing. The way to blend the devolved railway with the national railway is through going back to a national InterCity network, a London and South East network and a regional network – alongside the devolved nation railways (Scotland and Wales) and big city urban networks (London, Manchester, West Midlands etc). To help prevent non-devolved regional railways ending up as the bits and pieces that nobody wants, I’d establish a regional express network. The railway remains orientated around making radial routes out of London better and better whilst the service linking other cities can be very poor. Poor regional links often map onto areas of sizeable population which are relatively underserved by local rail too such as East Lancashire, Teeside and the East Midlands. A regional express network would open up new markets, bring some cache to the sector and make the national railway feel like it wasn’t as London-centric as it feels now. Meanwhile freight is supposed to be the big success story of privatisation. I’m not so sure. True it’s not repeatedly fallen apart like the privatised passenger railway but we are now left with a specialist bulk freight only railway which various companies scrap for at margins which leave no room for investing in expanding rail freights role into new markets. That’s why cities as large as Bradford have zero railfreight and why stations which could act as distribution hubs for urban deliveries stand empty at night. A nationalised railway should and could judiciously widen the role of railfreight in a way that would be both popular and capture the public and political imagination.

That’s my vision. Pick holes in it by all means. But some kind of vision (with proof points) along the way is what’s needed. And to do that I’d also argue that we also need a less Morrisonian concept of how the railway should be governed. The state corporation model is far better than what we have now. But with a state corporation a lot depends on who is the CEO. For every good CEO (like BR’s Sir Peter Parker) there’s plenty of examples of lost years under much lesser leadership. I’d therefore argue for the governance of rail to reflect a greater diversity of voices and perspectives than has hitherto been the norm. In the absence of public interest representation in the governance of a State corporation the civil service becomes the a poor proxy for the wider public interest.

Back in 1948 the nationalised railway nearly ended up being called Great British Railways. It staggered into being and took a long time to find its feet. This time there’s the opportunity not just to make the railway more reliable but also to set out a broader and more inclusive vision rooted in how best a national railway owned by all of us can best serve people, passengers and place. There is a world to win.

A pdf version of the Passenger Transport article can be found here

Illustration courtesy of Bring Back British Rail.