The battle of ideas over the best way to provide public transport is effectively over. Even the last Conservative government had given up on advocating for bus deregulation or anything remotely like the original rail privatisation vision. The new Labour government is far more enthusiastic about reversing both than the last Labour administration. Hence the quickening pace at which rail, trams and buses in Great Britain are coming back into the public sector – with direct public operation to the fore for steel wheel modes. Looking back bus deregulation was an early harbinger of the neo liberal period and rail privatisation one of its last full-throated hurrahs. Both were part of a much larger project where the objective was to break the power of organised labour in favour of the interests of organised wealth under the guise of the ‘marketisation’ of everything. The original objective of the wider neo-liberal project has now largely been achieved (though unusually the unions remain strong in the sector for industry specific reasons). We are now in a new era where having efficient and effective public transport is seen as a key underpinning for economic growth in an era of ‘securanomics’. The appetite and rationale for propping up pretend markets for rail and bus has now largely evaporated. After all the former is now mostly run by some form of publicly owned organisation (even if its overseas owned) and buses became a cosy, competition-averse, oligarchy long ago. Patience with the privatised railways periodic nervous breakdowns has also run out.

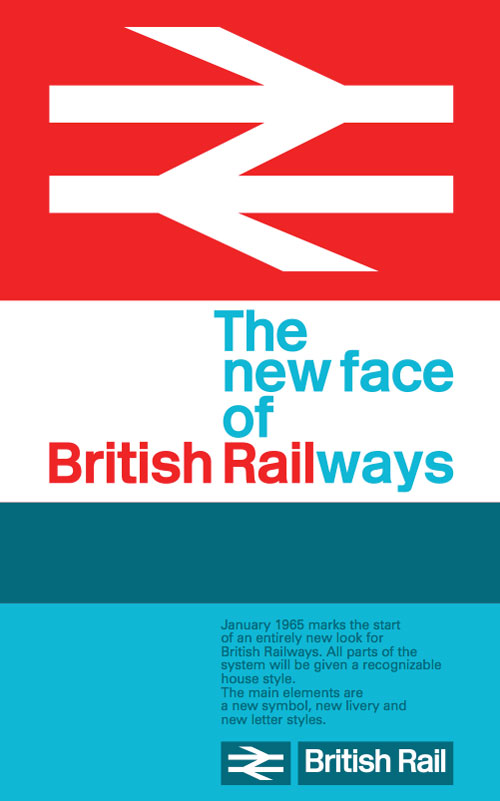

So in this new era the new big questions revolve around what will public sector control and operation look like in practice and whether the opportunities that are opening up will be fully realised. The current framing on rail reform is that this is a case of handing the railway back to industry professionals without all the tangled inefficiencies of privatisation getting in the way whilst simultaneously minimising day-to-day government interference. A more cohesive railway with less monetised interfaces and periodic nervous breakdowns is a good thing and long overdue. But if that is all we end up with then this risks nationalisation being a case of ‘meet the new boss, same as the old boss’ rather than an opportunity to think big – really big – about what a publicly accountable railway could be and do. A similarly cautious approach was taken to rail nationalisation in 1948 where British Railways (instead of Great British Railways as was also proposed) in its early years set about maintaining a geographically regionalised railway that looked backwards not forward. The governance, remit and senior appointments at British Rail ‘take two’ need to ensure that the railway doesn’t become introverted and its wider role in serving the social, economic and environmental needs of nations and their regions and places are reflected. What could thinking big look like? It should start with what a public sector railway is going to look like and feel like to the travelling public. At present what you get in terms of branding, train spec and comfort and so on is at the behest of different operators with very little that says to the public that this service is publicly owned or not. Instead shouldn’t a nationalised railway have a national intercity product which is consistent in terms of fares, train spec and service offer? We did it before with InterCity and many countries continue to do it – for good reason. This in turn could align with a national rail development plan which should incorporate what’s left of HS2 and all the unanswered questions it’s hacking back left behind. It was always mad to promote HS2 as a separate entity – when in reality it formed the basis for a rewriting of the national network. Now is the opportunity to integrate the future of new domestic high speed rail routes with the rest of the network and how it presents itself. An interminable process of fares reform has been going on for some time now – but its objectives are confused and the outcomes can be filed under tinkering. Greenpeace recently threw down a gauntlet calling for a UK variant of Austria’s successful 49 euro a month Climate Card. I’m not saying that this is necessarily the right approach. There’s the interplay with sub-national local bus and tram services to consider and the Greenpeace proposal doesn’t include InterCity – so perhaps something equivalent to Germany’s BahnCard might be. a better starting point (an annual subscription to get significant discounts on all rail travel). However Greenpeace have at least filled the vacuum with a bold proposition. What’s the big idea on fares on GBR that could grab the travelling public’s imagination? And when does the debate start? Also due some big thinking is the track access charge regime (welcome as the recently announced temporary alleviation for new freight services is) which is a relic of the faking of markets era. The format for track access charges was deliberately designed to dump disproportionate costs on regional trains (which have the least impact on infrastructure) in order to give rail freight a chance (fair enough) and create artificially ‘profitable’ long distance services. Finally, although it was undone by operational failings the foundations and early years of the Abellio Scotrail franchise is worth looking at as an example of an attempt to embed rail within a far wider set of social and public objectives. There was a director of economic development to forge better links with local authority economic development teams to make sure the railways mesh with both overarching local economic strategies but also with specific regeneration schemes and bids. It had a director of health and sustainability, fitbands for staff and an intention to achieve a gold award in the Scottish Healthy Working Lives. There was an employee gain share and a seat at the board for a trade union representative. Indeed the franchise specifically aligned itself with detailing how in practice the railway would contribute to the Scottish Government’s key aims. More widely the Borders Railway – the biggest domestic line reopening in a century was an exemplar of the ‘more than a railway’ approach. Rather than being an engineering project to walk away from afterwards there was joint working between Visit Scotland, Scottish Enterprise, TransportScotland and the local authorities in the area. This included a coordinated plan with an international tourism promotion campaign, an investment fund to support local business, a new business park at Tweedbank and a major housing development at Shawfair in Midlothian.

On bus, new legislation has begun the parliamentary process which hopefully will knock the rough edges of the 2017 Act to streamline the franchising process whilst allowing for municipal operation. However, it will be important to get this legislation through quickly (and its associated guidance) to avoid the risk of blighting implementation on the ground (whilst local authorities wait for the legislation). In my experience (with some honorable exceptions), officials have been institutionally biased towards deregulation and have dragged their feet as much as possible on getting all the regs and guidance done (eg the 2008 Local Transport Act and the 2019 Scottish buses legislation, which still hasn’t got all its regs and guidance in place). The powers to create new municipals is a good move. However, new municipals would still have to operate in a deregulated environment (where franchising is not being pursued) and thus could be undermined by private sector operators concentrating on the most profitable corridors. Meanwhile in a franchising environment they would have to compete with private sector operators (some of whom may put in loss leader bids) and they may not win on price. If they do win it may be because they have had to cut back on quality. And even if they do win the first round of franchising they may not win the second round. The legislation should therefore allow for direct award by authorities for municipal operation allowing the municipal to provide a locally accountable local bus service free from being undermined by cherry picking on-street competition. More thinking also needs to be done about the best formats for municipal operation given the mixed bag that is municipal operation at present. By and large owning local authorities have tended to be very hands off with their municipals – so they have all developed their own broadly commercial cultures. Is there a secret sauce behind why some of them are among the best bus companies in Britain? And to what extent can governance of the municipals better reflect the fact that they are companies that are locally owned with a public service remit? Away from the legislation the actual business of bringing bus services back under public control is happening on the ground. As bus franchising becomes more established the big questions for authorities are the pros and cons of a ‘plain vanilla’ approach to round one of franchising (in order to get something safely in place which can be built on later) or to look to be more innovative from the get go. Alongside this will be the tough choices about going for the cheapest bids for franchises or those where the bidder is motivated and offering quality at good value (even if its not the cheapest). After all we have seen many examples on rail franchising of the adage ‘if it looks too good to be true it is too good to be true.’

This is an industry which slants towards those looking backwards over their career and justifying what they did, and what they are used to, rather than those looking to the future and the scale of the opportunity that putting the public back into public transport opens up. On top of that the recent period of neo-liberalism hollowed out public sector capacity and confidence. For years it’s been a case of ‘there is no alternative’ to privatisation and deregulation. But now there is an alternative and we are starting to live it. Making the most or it is going to require guile, strategic thinking, confidence and ambition. And most of all looking forward not backward.