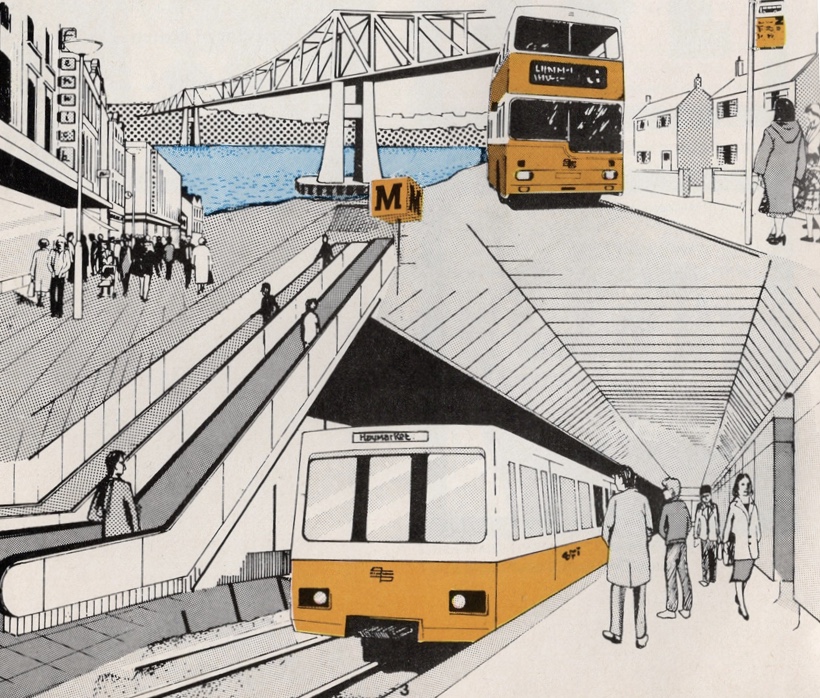

With the opening of the Northumbria line and the arrival into service of new Metro trains it feels like a good time to tell the story of Britain’s most progressive urban rail network…

There’s two key elements to a successful urban rail network – best use of emerging technology and local decision makers who embody the spirit of civic entrepreneurialism. That is the capacity to be quick thinking, bold and financially shrewd but with the good of the city as a whole in mind rather than narrow commercial gain. With that combination you can keep unleashing and renewing the potential of public transport to change places for the better. There is no better example of this than the Tyne & Wear Metro which for over 40 years has been the bone structure of the region’s identity, economy and daily life as well as Britain’s innovation railway. It’s a system too that is metamorphosing again – not just modernising but also potentially widening its scope and reach. Both the Metro’s uniqueness as a long standing, largely segregated light rail system and its distance far away from that there London is perhaps one reason why the Metro seems not to get the attention it deserves as an example of what public transport can be and do. Because after the London Transport roundel, the Tyne & Wear Metro’s ‘M’, must surely be the public transport logo and brand that is most integral to a British urban area’s sense of itself. Most integral too to how the city region operates – as alone amongst our cities, Tyne & Wear has a purpose-built, fully segregated light rail system that binds the area together. A system that makes not just journeys into the centre of the city the definition of simplicity, but radial and cross city journeys simple too. You can live in the suburbs of Newcastle and travel to work in the suburbs of Sunderland across the two city centres in as little as 40 minutes. A system that serves both the area’s major football clubs, its regional airport and all three universities as well as the business parks and residential areas that are strung along its lines, which are dotted with stations just 1.3 miles apart. It’s not quite an anywhere to anywhere service within the conurbation but it gets closer to achieving this in a seamless way, than most urban rail systems achieve. And it does this from early to late at attractive frequencies, seven days a week. It helps join the local dots throughout the week in an economical way too. Fares have been kept down to a level which local people can afford and which fit the facts on the ground about how the local economy works. So peak fares were abolished in 2014 because so many local people are on shifts or on zero hours contracts.

Affordable fares and the reach and utility of the network help explain why for a rail system this is no largely middle class preserve either – the user demographic represents the demographics of the region. And it’s not just the preserve of the able-bodied either – the system was built from the beginning so that wheelchair users could take advantage of it too. This is the railway that devolution built. A railway designed for local needs. Imagine how grim it would be if it had been remote controlled from London? In some ways you don’t have to imagine – rewind to the state of the local network when it was last part of the big railway in the 1970s and some of the stations were so run down they had no electricity.

It’s symbiotically Tyne & Wear’s railway, but the Metro is Britain’s innovation railway too. It’s local but it’s not parochial. The way it took a decayed heavy rail network and used it as the basis for a fully integrated urban transit network is arguably the most substantial transport innovation in a post-war UK city full stop. But it hasn’t stopped there. The Sunderland extension saw light rail trains sharing space with heavy rail trains on the UK rail network for the first time and it was the first network to have a pay-as-you-go smartcard system up and running outside London. This sits alongside numerous customer service innovation firsts – it was the first urban railway where mobile phones work in tunnels and the first to ban smoking. Alongside London it also has the largest commitment to public art of any transport provider – with over half of the stations covered. Alongside the artwork some of the stations are interesting or beautiful in their own right – from expansive seaside gems like Tynemouth to the 1970s brutalism of Chillingham Road. Some of the engineering is rather wonderful too – not least the sinuous realisation of the joys of pre- stressed concrete that is the Byker viaduct. The new trains now coming into service reflect the same values. Train design was based on extensive public input, local manufacturers and suppliers were involved in their construction and unlike the bleak and sterile interiors of many modern trains the new Metro trains have sensational art works by local artists as part of their fabric.

The new trains are part of a systematic overhaul and capacity improvements to what was an aging system leaving the way clear for expansion of the Metro alongside heavy rail. And there’s plenty of potential for that because as Tyne & Wear’s primal industries were taken out (coal, ship building, heavy industry) the railway network that served them also shrivelled. But not entirely. One way or another freight lines, redundant spurs and largely intact track beds are all there for the taking in terms of extending rail’s reach to where the unserved population centres are. Looking north the recently reopened Northumberland line has put places like Ashington and Blyth back on the heavy rail map. Looking south and the Leamside line (in effect an East Coast Main Line bypass from Gateshead to south of Durham) could be reinstated, in the process serving Washington (with a population of nearly 70,000). In addition, by branching off the Leamside line a Metro loop could be created by linking up with the line to South Hylton and onwards to Sunderland. Better services too are possible south of Sunderland on the current Durham coast heavy rail line and south along the East Coast Main Line corridor using former freight lines – as well as eastwards on the Tyne Valley line.

The Tyne and Wear Metro was a modernist marvel when it emerged from the wreckage of the local rail network in the 70s. Exhibiting the boldness and big thinking you would be more likely to see in a city in France, Sweden or America in that era. It’s both an international exemplar and Britain’s innovation railway. But at the same time distinctively and deliberately Tyne and Wear’s railway – always alive to the needs of local people and the local economy. With its fabric renewed and bus franchising on the way Britain’s most progressive railway has the opportunity to be once again part of the wider integrated public transport network it was built to be.